Have you ever wondered why young children often forget (or totally refuse) to put on a coat before leaving the house on a snowy day?

As an adult, the choice to put on a jacket on a snowy day may appear obvious to you, but this seemingly straightforward decision arises from a surprisingly complex interplay of behaviors.

If you are interested in knowing more about the underlying mechanisms of such a goal-driven behavior, stay with me for the rest of this blog post.

Let’s closely examine the elements of the behavior mentioned earlier. In order for a child to successfully wear their jacket:

- They need to keep a goal in mind (staying warm and dry) even though this goal may not seem immediately relevant in the comfort of a warm house.

- They must resist the impulse to follow the regular sequence of tasks (like putting on socks and shoes to head out the door) and instead adjust their routine to include something new (pulling a coat from the closet).

- Unless someone intervenes, this deviation from the usual routine must be accomplished without any external reminders (like a visible coat, or a timely reminder from a caregiver).

Looking at the components of this simple decision, it’s no wonder that for a younger child, there’s a lot involved in order to successfully navigate it.

To successfully tackle each of these tasks, children must engage in a set of cognitive processes known as executive functions (EFs). If you’re already familiar with this term, great! However, if it’s a bit elusive, don’t worry—you’re not alone. Much like many other concepts linked to behavior and learning, defining executive functions is no simple task.

In this post, we want to examine this concept more closely together.

To start, let’s watch this short introductory video, from the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University:

As also discussed in the video, we can think of executive functions as the “brain’s air traffic control system” (Center for the Developing Child, 2011). Executive functions are the cognitive control processes that regulate thought and action in support of goal-directed behavior. In order to do so a child has to manage lots of information and avoid distractions.

Executive functions depend on three types of brain functions:

Working memory

Selecting and keeping goals, information, and plans in mind and using them to guide cognition and behavior.

Inhibitory control

Focusing attention, ignoring distractions, and set priorities and resist impulsive actions and responses.

Cognitive Flexibility

Sustaining or shifting attention in response to different demands or to apply different rules in different settings, considering multiple ways to represent and solve a problem, taking the perspective of others, and making inferences.

Looking at the preceding example of wearing a coat on a snowy day, we can distinguish how all these functions should operate in coordination with each other for the successful application of executive function skills.

Now, Let’s take a look at our brains to explore more closely the brain structures that are associated with executive functions:

The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC – the front part of the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex) is the brain region linked to the executive functions.

The PFC is an important and specific part of humans brain made us capable of many of the higher order cognitive abilities that are necessary to peruse and achieve a goal. This brain region is the most recently evolved brain region. It is also part of the cortex that is more highly developed in humans than in other primates. If you are interested to know more about PFC, you can take a look at this short video.

There is an interesting story behind how they first found out the association between PFC and executive functions. According to Cristofori and Colleagues (2019), this association originated in the famous case of Phineas Gage, who was working on a railroad construction site when in 1848 a large iron rod passed through his left frontal lobe. Phineas Gage survived this accident, but his behavior and personality were dramatically altered. He is reported as having permanently lost his inhibitions, so that he started to behave inappropriately in social situations. The brain finding related to his case provided the first documented evidence for the complexity of EFs and their neural basis

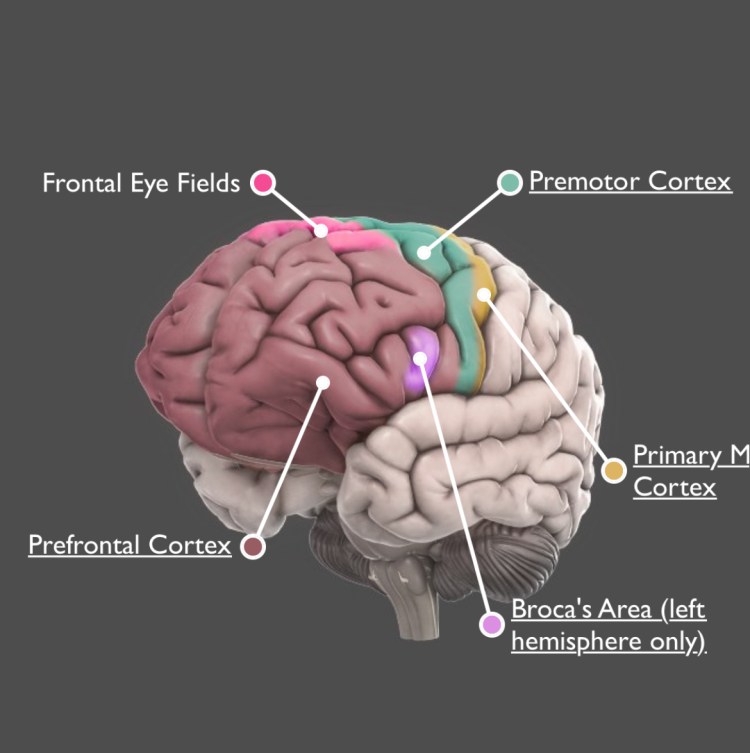

Although this brain region is most commonly associated with EFs, it is not solely responsible for everything that we know as executive functions. This region does not act alone. the prefrontal cortex is involved in controlling our behavior through its interaction with all other parts of the brain. The following picture illustrates how different regions of the brain contribute to various sub-functions of executive function. Through their harmonious work, these brain areas enable us to employ these higher order cognitive abilities.

You might ask yourself why does it matter? Why is it helpful for me, as an educator, to know about executive functions ![]()

Actually, we can consider the development of EF skills a quality-of-life matter. Children’s executive functions are key ingredients in their life performance. We all need to get things done to be happy and successful.

Research over the past decade or so has shown that executive functions are critical, early predictors of success across a range of important outcomes, including school readiness in preschoolers, as well as academic performance at school entry, and beyond. Individuals with weaker executive functions during childhood tend to experience lower levels of health, wealth, and social well-being in adulthood compared to those with stronger executive functions. It is also interesting to know that the roots of executive functioning skills can be seen as early as infant and toddler years.

Another important point here is that executive functions change over the life course, however, they improve radically over the first few years, making children’s first years of life a window of opportunity for the development of executive function skills. This can happen via well-timed, targeted scaffolding and support provided by parents, caregivers, and educators.

Here is where you as an educator can step in, and your role would be vital.

We earlier discussed that EF is a predictor of children’s success for example in terms of school readiness and academic performance. In fact, EF can be a better predictor of academic and social emotional success than IQ. And more importantly, unlike IQ, EF skills are trainable. They can be improved through reflection and practice.

Children aren’t born with these skills, they are born with the potential to develop them. It is also important to notice that some children, especially those who have experienced adversity may need more support than others to develop their EF skills. Adverse environments can subject children to toxic stress, which can disrupt their brain structure, and hinder the development of executive function.

Our role as educators even become more important when considering the results of a research study on everyday manifestation of EFs in preschool settings by Moreno and colleagues. The findings revealed that:

1) EF and EF-support behaviors are occurring with low frequency in preschool settings.

2) Children are more engaged in organized thinking than teachers actively supporting it.

3) Teachers’ presence, particularly when facilitating expanded play, positively influences children’s real-time EF behaviors.

If we, as educators, do not recognize the presence or absence of EF in context, our ability to support and enhance it will be left to chance. Therefore, the first step is to understand what executive function looks like, and more importantly how to encourage it in everyday preschool activities.

For the rest of this blog post, we will spend some time together reviewing some practical suggestions which will assist you in scaffolding opportunities for children to practice and develop their executive functions.

For children, three key domains of behaviors have been known to be pivotal for executive function development:

(1) engaging in mature dramatic play,

(2) utilizing metacognitive language and narrative talk,

(3) participating in diverse object play.

For teachers, three primary domains of adult behaviors emerged as being EF-promoting:

(1) Providing meta-cognitive support (helping children to think about their thinking, or the processes they are using as they engage in tasks),

(2) fostering concept development,

(3) and environment- or activity-structuring.

You can utilize these domains as a guiding tool to integrate opportunities for your students within their daily activities to support the development of their executive functions. Also remember that to improve executive functions, focusing narrowly on them may not be as effective as also addressing emotional and social development. Therefore, crafting a supportive environment would always be the first step.

One more thing:

Research findings also indicate that spending time in nature can significantly contribute to the development of children’s executive functions. Therefore, a potential strategy to augment opportunities for enhancing EFs in children is to provide them with more time for free play in natural environments. I’m confident that many of us have witnessed the myriad opportunities nature affords for children to engage in imaginative play, active exploration, and the abundant use of loose parts for activities such as matching and sorting games. Additionally, the tranquil setting of nature provides a conducive space for children to rejuvenate their attentional capacities during moments of quiet reflection. As discussed earlier, these activities are widely recognized for their effectiveness in fostering the development of children’s executive function skills.

Lastly, remember that getting better at something usually happens when we keep practicing and persisting in the things that are important to us. That is also true for the development of executive functions in children. Repeated practice is the key.

So, don’t forget to keep up the good work!

Additional Resources:

^ If you are interested to know more about EF and the brain regions associated with it, you might find this resource helpful.

^ Here is another informative video for you to watch, if you are interested to deepen your understanding of executive functions.

^ Also, you can take this free self-pace course to enhance your knowledge about executive functions.

REFERENCES:

– Barker, J. E., Semenov, A. D., Michaelson, L., Provan, L. S., Snyder, H. R., & Munakata, Y. (2014). Less-structured time in children’s daily lives predicts self-directed executive functioning.Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00593

– Barker, J. E., & Munakata, Y. (2015). Developing Self-Directed Executive Functioning: Recent findings and future directions. Mind, Brain, and Education, 9(2), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12071

– Barrasso-Catanzaro, C., & Eslinger, P. J. (2016). Neurobiological Bases of Executive Function and Social-Emotional Development: Typical and atypical brain changes. Family Relations, 65(1), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12175

– Blair, C. (2016). Executive function and early childhood education. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 10, 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.05.009

– Carr, V., Brown, R. D., Schlembach, S., & Kochanowski, L. (2017). Nature by Design: Playscape Affordances Support the Use of Executive Function in Preschoolers. Children, Youth and Environments, 27(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.27.2.0025

– Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2011). Building the Brain’s “Air Traffic Control” System: How Early Experiences Shape the Development of Executive Function: Working Paper No. 11. Retrieved from www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

– Cristofori, I., Cohen-Zimerman, S., & Grafman, J. (2019). Executive functions. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology (Vol. 163, pp. 197–219). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804281-6.00011-2

– Diamond, A., & Lee, K. (2011). Interventions Shown to Aid Executive Function Development in Children 4 to 12 Years Old. Science, 333(6045), 959–964.

– Fassbender, C., Murphy, K., Foxe, J. J., Wylie, G. R., Javitt, D. C., Robertson, I. H., & Garavan, H. (2004). A topography of executive functions and their interactions revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Cognitive Brain Research, 20(2), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.02.007

– Friedman, N.P., Robbins, T.W. (2022). The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacol. 47(1), 72–89 . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-01132-0

– Moreno, A. J., Shwayder, I., & Friedman, I. D. (2017). The Function of Executive Function: Everyday Manifestations of Regulated Thinking in Preschool Settings. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(2), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0777-y

– Schutte, A. R., Torquati, J. C., & Beattie, H. L. (2017). Impact of Urban Nature on Executive Functioning in Early and Middle Childhood. Environment and Behavior, 49(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916515603095

– Wiebe, S. A., Sheffield, T. D., Nelson, J., Clark, C. A. C., Chevalier, N., & Espy, K. A. (2011). The structure of executive function in 3-year-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 108(3), 436–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2010.08.008